Investment Insights

Outlook 2025

Welcome to EFG’s Outlook 2025 where we outline our top ten themes for the year ahead and review how well our predictions for 2024 did.

| Download EFG’s Outlook 2025 publication | |

|---|---|

| Outlook 2025 |

We anticipate three significant challenges to global economic growth in 2025.

1. First, president-elect Trump’s planned tariffs on US imported goods. The possible imposition of 60% tariffs on US imports from China and 10%-20% on imports from the rest of the world, coupled with likely retaliation, would be a clear threat to world growth. One estimate puts the hit at around 0.3% in 2025.¹ Notably, the impact on US growth could be similar to that on China (a 0.6% reduction), as higher import costs depress US real incomes. Europe, particularly Germany, could be badly affected because of its auto exports to the US. Generally, uncertainty about trade relationships could have broad and long-lasting implications.

However, world gross domestic product (GDP) growth is no longer as dependent on trade growth as in the past (see Figure 1): domestic demand has become more important in driving growth for many economies. Furthermore, it could be that such tariffs are not fully imposed or are circumvented. Exports to the US could be ‘voluntarily’ restricted by the exporter or limited by quota, for example. Exchange rate movements can offset the tariff impact and most currencies have already weakened against the US dollar since Trump’s election. Exports can also be redirected via ‘connector countries’ with lower tariffs (see Figure 2). These factors may mean that exports to the US are less affected than initially thought but they will all have detrimental consequences for the exporting countries. For example, a depreciation of the renminbi may raise inflation in China; and countries with large manufacturing sectors, such as Germany, would see their growth prospects hit.

Certainly, the US can function better than other economies from a more restricted trade environment, for several key reasons. First, it is largely energy independent; it was much less affected by the energy price shock after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine than other advanced economies, for example. Second, it is a highly innovative economy and has an exceptional ability to turn this into business opportunities. High spending on Research and Development (R&D) has been a key strength of US companies (see Figure 3). Third, the US has access to plenty of labour from abroad, even though restrictions on that may well be imposed. Fourth, the US is a relatively closed economy for which trade represents a much smaller share of GDP than in Europe and Asia. For these reasons, it seems likely that the US will continue to lead advanced economies’ growth in 2025.

2. The second headwind reflects ongoing problems in the Chinese economy. Structural weaknesses in the property market, high local government debt and poor consumer confidence cannot be quickly resolved. Policy easing can help, but the magnitude may be insufficient to produce a meaningful reinvigoration.

3. Indeed, around the world, the degree of policy easing may prove disappointing in 2025. The scope for further policy interest cuts is seen as relatively limited – less than one percentage point in the US and Switzerland and slightly more than that in the UK and the eurozone. Certainly, tight monetary policy has proved successful in returning inflation to target and the lagged effects of lower interest rates in boosting growth should become evident later in 2025. However, as attention turns to fiscal policy, the concern is that it is constrained in many economies by high deficits and debt levels.

The scope for fiscal easing is not great. But that, in itself, is behind the need for government reform. In the US, the new Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), led by Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy aims to cut USD2 trillion from government spending over ten years, an amount equal to the government’s annual discretionary spending. Such reforms have echoes of the rolling back of the state’s role, seen in the 1980s. At the other extreme, a new German government may well ease the restrictions on government borrowing. There, and indeed across Europe, are pressures for much higher spending on decarbonisation, digitalisation and defence, as identified in the Draghi Report.

After what may well be an uncertain period for the global economy in the first half of 2025, we see a better second half of the year and further improvement into 2026.

1 Source: Aurélien Saussay, “The economic impacts of Trump’s tariff proposals.” LSE Grantham Institute Policy Insight October 2024

The BRICS group will gain increased global significance in 2025 for three main reasons.

1. The group is getting bigger. Initially comprising four economies – Brazil, Russia, India and China – they were joined by South Africa in 2010 and Iran, the United Arab Emirates, Ethiopia and Egypt at the start of 2024. Together these nine economies have a population of 3.6 billion people, 45% of the world total (see Figure 4). For most of the time BRICS has existed, China has been the largest economy in the group. But India is catching up, helped by the fact that its population now exceeds China’s. At Purchasing Power Parity exchange rates, the combined GDP of the BRICS is USD73 trillion, more than a third of the world total. The group is likely to expand further with Malaysia, Thailand and Turkey all seeking membership and Saudi Arabia considering its invitation to join.

2. The BRICS grouping is now making a large contribution to global economic growth. The world economy is forecast to grow by 3.2% in 2025, according to the IMF. Half of this growth will be generated by the BRICS. The G7 major advanced economies will contribute to just 15% of the growth, with the bulk of that coming from the US (see Figure 5).

In a world in which trade patterns risk becoming more fragmented, trade between the BRICS can be expected to become even more important. Indeed, the pressures of global trade fragmentation provide an incentive for the BRICS to co-operate to a greater extent. The natural resources of Brazil, Russia and Iran have always made those economies attractive partners for China. But as world trade looks set to become increasingly dominated by technology and services, it remains to be seen how well the BRICS members can help each other. India and China seem to be competitors rather than enthusiastic collaborators.

3. The BRICS have agreed to pool USD100 billion of foreign-currency reserves and have formed the New Development Bank, headquartered in Shanghai. Since it started operations in 2015 it has approved almost USD33 billion of loans — mainly for water, transport and other infrastructure projects. However, the Russia-Ukraine war saw the bank freeze Russian projects and Russia has not been able to access dollars via the shared foreign-currency system. Member countries seem to have prioritised access to the dollar-based financial system over helping Russia. Russia has proposed changes to cross-border payments between BRICS countries but how much traction this proposal gathers remains to be seen. A BRICS currency, to rival the US dollar, seems highly unlikely, especially as it is opposed by Trump.

Of course, the global geopolitical situation – especially the role of Russia – acts as an impediment to co-operation within the BRICS. 2025 may well, however, see an agreement to end the war in Ukraine. Such a deal would likely include three elements: a buffer zone between Russia and Ukraine; an agreement for Ukraine not to join NATO; and a lifting of at least some sanctions on Russia. That seems workable, although maybe not on the ambitious timetable (“within 24 hours”) proposed by president-elect Trump.

With the battle against inflation largely won (indeed, it may well fall further and undershoot targets, especially if there is fiscal consolidation), 2025 will be a year when the focus of policy turns to employment.

Unemployment levels in the major advanced economies are not particularly high, but they are above the lowest rates seen in recent years (see Figure 6). Furthermore, participation rates – the proportion of working-age people employed or actively seeking work – are worryingly low in some economies.

Such a shift of focus is facilitated in the US by the fact that the central bank has a dual mandate: to achieve price stability and maximum employment. Indeed, pre-Covid, when inflation had been low and stable for some time, the Federal Reserve openly supported a policy of running the economy ‘hot’ to create more jobs. This can be seen in the rise in the ratio of vacancies to unemployment from the mid-2010s up until the pandemic.

In its strategy statements, the Fed has not explicitly defined ‘maximum employment’. Indeed, it is probably very hard to define precisely and will almost certainly change over time owing largely to factors that affect the structure and dynamics of the labour market.

Nevertheless, the Federal Reserve plans, during 2025, to conduct a new review of the statement of longer-run goals and monetary policy strategy. A similar exercise was concluded in August 2020. The path to a more explicit statement about employment is open.

Other central banks have dual mandates, but none explicitly include an employment objective. The Bank of England, for example, has a primary monetary policy objective to keep inflation at 2% over the medium term, with support for the government’s other economic aims a secondary objective. It is possible, although unlikely, that the inflation target could be changed – it is set by the government. There is the potential for a higher target rate of inflation, allowing lower interest rates and possibly a boost to growth and employment.

Around the world the promotion of higher employment is much more likely to be achieved by direct measures to promote employment rather than indirect monetary measures. The need to do that is even more important in several emerging economies, especially in Africa, where unemployment rates remain stubbornly high.

The European Central Bank and the Swiss National Bank, of course, have just a single mandate: price stability. It is notable that, relative to the US and UK, both have lower interest rates than pre-pandemic.

Government budget deficits and debt levels (accumulated deficits over time) around the world are high. Global government debt has reached USD100 trillion and is projected by the IMF to rise to 100% of GDP by the end of the decade (see Figure 7). In the US and China debt levels are already around that 100% level. After the global financial crisis such debt levels were widely considered as unsustainable and many governments took action to stabilise or reduce debt.

High debt ushered in a period of austerity: notably, measures to reduce government spending. That is not likely to be repeated in current circumstances. There is an intolerance for austerity almost everywhere.

To assess the debt and deficit situation in different countries we can look at three key aspects of the situation.

1. First, is the level of government debt below 100% of GDP or not? Above that level was seen as a problem after the global financial crisis because it was considered the level beyond which economic growth would be impaired. But the concern has a longer pedigree: for some time it has been seen as the level at which a snowball effect would mean debt levels spiral out of control, mainly because of the need to pay interest on the accumulated debt. That is, indeed, a current concern in the US, where interest payments on government debt are estimated at USD1 trillion in fiscal year 2025, 20% of government revenue.2 Encouragingly, of the 21 economies listed in Figure 8 (the G20 plus Switzerland) fifteen have debt levels below 100% of GDP in 2025.

2. The second question is whether the debt ratio is stable or falling. Even if it is above 100%, a stable or falling level can be regarded as less of concern. Eleven of the 21 countries in Figure 8 have debt below 100% of GDP and a debt level which is stable or falling as a share of GDP. We give them an “A” grade.

3. The final question is, if the debt ratio is not stable or falling, whether corrective measures are feasible. The measures involve either deficit reduction by increasing revenue or decreasing spending; or boosting nominal growth – by increasing real GDP growth or tolerating higher inflation.

The combination of these factors determines our assessment of debt sustainability. Take the UK as an example: its government debt is above 100% of GDP; it is still rising in the coming years; but measures to stabilise the debt level can realistically be made. For the UK, a modest further reduction in the budget deficit would suffice to stabilise the debt ratio.

For the US and France, however, the situation is worse. In France, there are clear limits to raising taxes further, given the already very high tax burden. There is a real risk that continued high government spending cannot be reasonably addressed and this crowds out the private sector. In the US, president-elect Trump’s approach of radical transparency and the establishment of the DOGE represents a bold attempt to tackle a bloated public sector. It remains to be seen how effective it will be and whether indeed other countries use a similar approach if it shows early success.

2 Source: CBO June 2024 Budget projections

The adoption rate of generative AI has been rapid. 40% of users in the workplace now use it, according to one study.³ That is twice the adoption rate of the internet at a similar stage after its introduction. Generative AI is quickly becoming a mainstream technology and 2025 will be a year in which it progresses much further. That may well be the start of a multi-year development in the industry. Jensen Huang, Nvidia CEO, has claimed the computing power driving advances in AI will see a fourfold increase annually. That would be a millionfold increase over the next decade.

There is always a degree of hype surrounding new innovations, of course. Sometimes it is justified by future developments. The current extent to which the internet is used is way beyond the expectations at the time of the initial public offerings of Amazon and Google in 1997 and 2004, respectively.

The US is very much the leader in investing in AI (Figure 9) with China and Europe far behind, according to one estimate. This provides an important source of strength for the US economy, especially if, as we expect, it feeds through to higher productivity growth. Estimates of the potential impact on productivity growth are, however, very diverse.

AI is a disruptive technology and, as with all such developments, there will be inevitable changes in employment. The switch from the current, widely-used CPU chips in computers, cars and cloud storage, to GPU chips which are used for AI and machine learning is one such change.

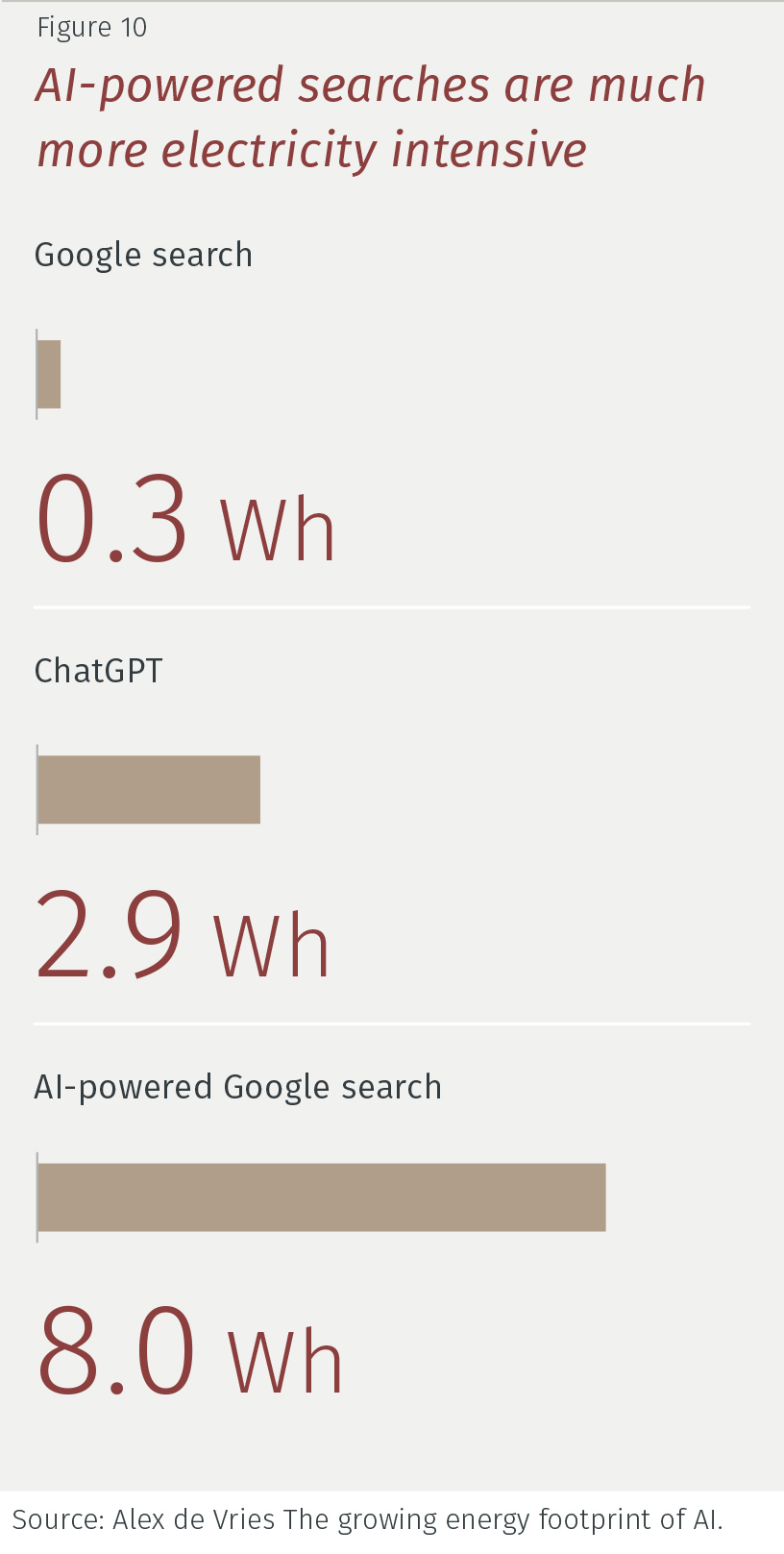

One important concern stemming from this is that AI technologies are very energy-intensive. They will place additional demands on electricity generation in a world which is already transitioning to greater electricity use (in transport, with electric vehicles; in industry, with a move away from fossil fuels; and in domestic use, for air conditioning and heating). That leads us to our next main theme, the growth of electricity demand and how this will be met.

3 Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis.

In the coming years, global electricity demand will be supported by the ongoing electrification of housing, transport and industry as well as a notable expansion of data centres. The share of electricity in final energy consumption is expected to continue to rise: from 18% in 2015, to 20% in 2023 and 30% in 2030 (on the IEA’s Net Zero Emissions by 2050 Scenario, a pathway aligned with limiting global warming to 1.5°C).

Electricity consumption from data centres, AI and the cryptocurrency sector could double between 2023 and 2026, reaching 1,000 terawatt-hours (TWh) in 2026. That would be equivalent to the current electricity consumption of Japan; and it would be similar to the expected electricity needs of all electric vehicles on the road in 2030.

The electricity consumption of AI and AI-enabled searches is far higher than standard searches: ten times as high or even greater. On the basis of expected rapid growth in AI-related searches, various tech companies have sought to invest in nuclear electricity generation from either the re-commissioning of standard nuclear generating capacity which may have been mothballed or from the new technology of small modular reactors (SMRs). SMRs are designed to be compact, simple to construct in a factory and then transported and assembled on site. When used to power data centres they are typically co-located with them. SMRs have a generation capacity typically of a few hundred megawatts (MW). So, several SMRs running together would have a capacity similar to that of a traditional nuclear power plant (700-1000 MW). Given that nuclear power can generate electricity almost continuously, the electricity generated from a 1000 MW system would be close to 1,000 TWh per year.

We see an important national security angle to this development. The US generates almost a fifth of its electricity needs from nuclear but the proportion is much higher in several European countries and South Korea. That puts them at a relative advantage to countries such as Germany, that have phased out their nuclear energy programmes, a process that intensified after the Chernobyl nuclear power plant explosion in 1986 and the Fukushima disaster in 2011.

Nuclear capacity is being added at a very high rate in China (see Figure 11). Nuclear power electricity generation either under construction, planned or proposed, amounts to more than 2000 TWh, similar to the world’s total electricity generation from nuclear in 2023. If that is put in place, there will be another new dimension to China’s relative advantage over other major economies.

Corporate earnings generally grow over time as a result of the nominal growth (real growth and price increases combined) in the economy. That, in a sense, is the ultimate driver of the ‘top line’ or ‘revenue’ growth of all companies. For US S&P 500 companies, this trend is demonstrated in Figure 12. The long-term growth of S&P 500 earnings per share is shown alongside the S&P 500 index. The right-hand axis, showing the price index, is 20× the left-hand axis, showing earnings per share. So, if the two series moved exactly in line with each other, the S&P 500 index would consistently trade at a price/ earnings (P/E) multiple of 20. Of course, that is not the case. The pattern is not a smooth one. There are clear variations from year to year, when the price index becomes high or low relative to the earnings level. But the general trend is evident.

Over shorter periods, however, how earnings growth compares with expectations – often termed the ‘earnings surprise’ – is correlated with S&P 500 returns (with a correlation co-efficient of 37% over the period 1 January 1989 to 5 November 2024). We take expected earnings as the trend rate of growth of earnings, rather than the expectations at the start of each year – which can be highly volatile.

Several years are worthy of highlighting. In 2021, earnings were significantly ahead of expectations and the S&P 500 produced returns of 27%. The following year, earnings disappointed relative to expectations and returns were minus 20%. In the last two years, earnings have been broadly in line with expectations and the S&P 500 has produced gains of over 20% in each year.

Looking ahead, this suggests the key to returns is whether earnings expectations for 2025 are realised. Current expectations are for 10% growth in 2025, a little above the long-term trend growth in earnings (6% p.a. over the last ten years). One concern about whether such earnings growth will be attained is the degree of concentration in the US stock market, our next main theme for 2025.

The top 10 companies in the S&P 500 index currently account for 35% of its market capitalisation. The market is therefore more concentrated than it has been for many years. Such a level of concentration has not been seen since the end of 1962, when AT&T alone was over 10% of the S&P 500. There has been a good deal of commentary warning about the dangers of such concentration, especially given the high P/E multiples of those top 10 stocks. We would make three main points, which indicate that this is not a problem in itself but rather raises issues about the valuation and performance of those large companies relative to the rest of the market.

1. With reference to that earlier period of high market concentration in the 1960s, from the end of 1962 (when the market capitalisation of the top 10 stocks first exceeded 35%), the S&P 500 gained an additional 50% until an eventual bear market started in February 1966. So, it was over three years before the feared bear market materialised.

2. The valuation of the largest ten stocks cannot properly be judged on a simple metric such as the historic price/earnings ratio. Rather it needs to take into account prospects for revenue and earnings growth, cash flow, reinvestment needs, the competitive landscape and any multiple expansion or contraction.

3. Not owning the largest stocks is, in itself, a somewhat risky strategy for those assessed against the performance of a broad US stock market index. Not owning such stocks involves a large tracking error risk.

The last time we witnessed strong US equity market performance based on a small number of stocks was in the late 1990s. That was the time of the TMT (technology, media and telecom) and ‘dot com’ boom. That boom turned to bust in the early 2000s. Figure 13 shows an interesting parallel between that period and now. The S&P 500 index rose by 215% in the six years from 1 January 1994 to 1 January 2000. The overall gain ran ahead of the increase in earnings (101%) and the P/E multiple of the overall market expanded from 20.2 to 31.6.

In the six years starting on 1 January 2019, the S&P 500 has gained 139%, much less than in that earlier 6-year period. Earnings growth has been only half as strong as in the late 1990s. As a result, the P/E multiple has expanded at almost the same rate in the two periods. On that basis, the time does not seem ripe for an impending correction in the market.

Having said that, there are relatively better opportunities elsewhere in the broad US equity market. We see a favourable prospect in small and mid-sized companies in growth areas of the market (notably technology) where valuations are more reasonable than those of the large cap stocks. Additionally, such companies may well benefit if president-elect Trump pursues an agenda of breaking up larger companies on competition grounds.

The consumer discretionary sector is our favoured area of the US and global equity market for 2025. We see three broadly supportive economic fundamentals for that sector in 2025.

1. First, wage and employment growth are likely to hold up well in most economies. Wages should grow in real terms, as a result of nominal wage gains (which in themselves were a lagged response to past high inflation) running ahead of inflation, which itself will fall further. We see that phenomenon in the US, UK, across Europe, Japan and in China.

2. Second, on our estimates, in the eurozone, UK, China and Canada, consumers still have some accumulated excess savings after the pandemic (see Figure 14). These excess savings have, however, been largely eroded in the US and the current savings rate is low. However, in the US, consumers have enjoyed stronger wealth effects from rising equity and housing markets. Indeed, these accumulated wealth gains in the US are much larger than excess savings at their peak. In the third quarter of 2024, household net worth was as much as USD46 trillion higher than immediately pre-Covid.

3. Third, falling interest rates will benefit consumers, particularly in the UK where a greater proportion of borrowing is linked to short-term interest rates.

In the consumer discretionary sector, valuations are close to fair value on the basis of our proprietary model. This takes into account seven valuation measures. That fair value assessment is for the global consumer discretionary sector, which reflects relatively higher valuations in the US and lower valuations in Europe, UK, Asia and Japan. Other sectors are either more expensively valued or lack fundamental support.

There are two interesting areas of opportunity we see in fixed income markets for 2025.

1. First, we think there will be a general tendency for yield curves to steepen, particularly in the US (see Figure 15). Such a view is quite widely held. The conventional explanation is that there will be more short-term interest rate cuts by policymakers as inflation recedes further; and that there will be upward pressure on long-term bond yields as a result of high, and potentially rising, government deficits. However, in three of the last four yield curve steepening episodes, the dynamics have been different. In 1989-92, the yield curve steepened from -18 basis points to +389 basis points. But the steepening was predominantly due to a very large fall in short-term rates (from 8% to 3%) with 10-year yields also falling (from 7.8% to 6.8%). A very similar pattern was seen in 2000-2002 – when short-term interest rates fell to 1% and 10-year yields remained little changed; and in 2007-2009 – when short-term rates fell to zero and 10-year yields dropped from 4.7% to 3.8%.

The Covid-era yield curve steepening was the only one of the last four steepenings which saw 10-year yields rise. Arguably, that was because of a slow response by the Fed to rising inflation – a mistake they are unlikely to make again. On balance, that leads us to think that although a yield curve steepening is likely, it may well not develop because of a significant rise in 10-year yields. We expect that it is likely to be mainly driven by reductions in policy rates.

2. The second area of opportunity is in government bond yield spreads. In the eurozone, government bond yield spreads have widened over Germany, notably for France. The Italian bond yield differential is even wider. On the basis of the relative deficit and debt fundamentals described in Theme 4, we expect the French market to underperform its eurozone peers.

There are spread-related opportunities in corporate and high yield markets, but sector and company selection are more important than ever in an environment characterised by political and competitive change. We also continue to see opportunities in emerging market hard and local currency debt, given the stronger environment we envisage for the BRICS.

How we did in 2024

Overall score:

7/10

| Theme | Result |

|---|---|

|

1. World economy has a soft landing |

Correct |

|

2. Productivity gains |

Correct |

|

3. Fiscal fragility |

Correct |

|

4. Political turbulence |

Correct |

|

5. Demographics is (still) destiny |

Correct |

|

6. Weight loss and consumer staples |

Partly correct |

|

7. Clean energy transition |

Partly correct |

|

8. Undervalued currencies recover |

Incorrect |

|

9. Bond opportunities |

Correct |

|

10. Favour small cap stocks |

Incorrect |

-

Result

Correct

-

Result

Correct

-

Result

Correct

-

Result

Correct

-

Result

Correct

-

Result

Partly correct

-

Result

Partly correct

-

Result

Incorrect

-

Result

Correct

-

Result

Incorrect

For a long-term outlook, discover our Capital Market Assumptions here.